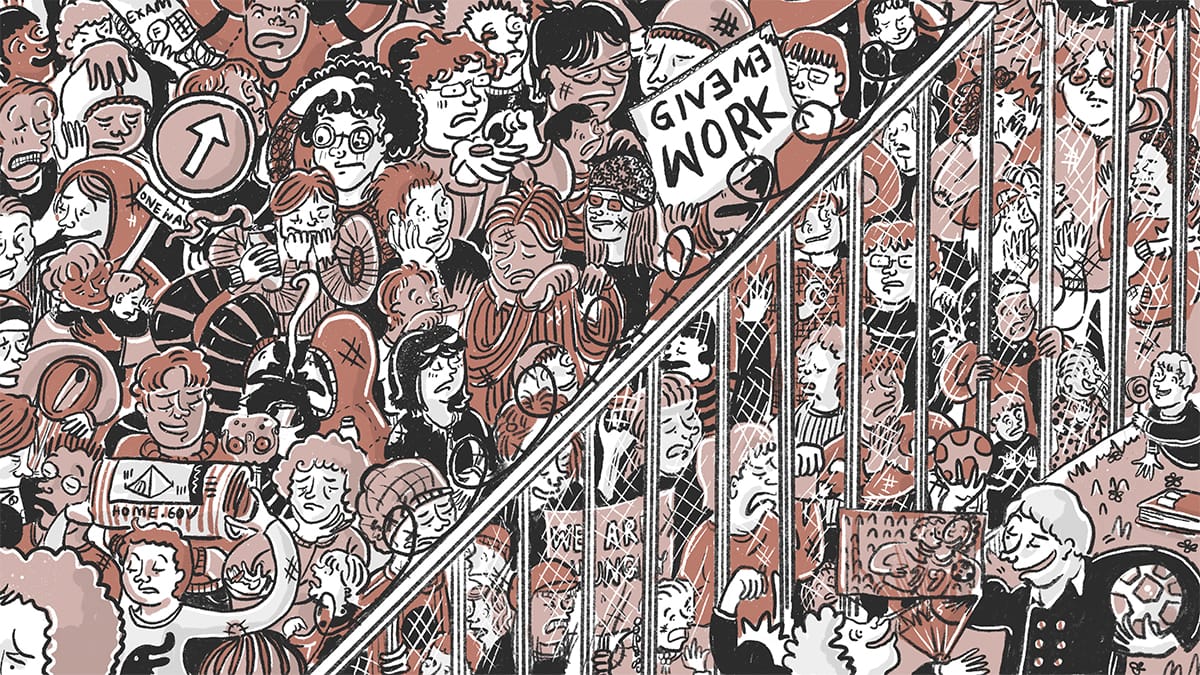

England is a country with entrenched inequalities. There are ever-widening gaps between rich and poor, North and South, privileged and less-privileged. The level of wealth inequality between the richest and poorest people in England is the highest in the developed world.

Many neglected regions in England, particularly in the North, have experienced half a century of stagnation and decline, while London and the South-East continue to benefit from private-sector growth. Many children and young people live in households in which parents are forced into low-paid and insecure work.

People with protected equalities characteristics - race, ethnicity, ability, gender, sexual orientation, religion - face even greater discrimination today with the gradual dismantling of protections, meaning worse life outcomes than straight, white, able-bodied men (SWAMs).

Decades of welfare cuts have created a significant segment of the population living in absolute poverty, forced to rely on food banks and other forms of charity to get by. These conditions have worsened with the food and medicine shortages, which have pushed prices out of reach for low-income families.

Doctors are seeing higher levels of malnutrition amongst children and young people, due to a lack of fruit and vegetables in their diet (which are too expensive for many to buy). There has also been a return of several ‘Victorian-age’ diseases due to poor nutrition, poverty, and people being forced to live in squalid, cramped conditions - including polio, tuberculosis and rickets.

Children from deprived backgrounds are more likely to enter the prison system than the job market, and are more likely to experience mental health difficulties throughout their lives. They are also more likely to have been excluded from the school system - where privatisation has eroded the quality and existence of state schools - and are therefore more likely to be illiterate, significantly reducing their job prospects.

In contrast, in the affluent areas across England, young people have life experiences that are radically different from those in deprived areas. Living in private housing, with access to expensive high-quality food, private medical and dental care, and private schooling, wealthier young people have been unaffected by the economic recession.

Becoming very popular in the 2020s, affluent, middle-class parents routinely set up extensive off-shore investments, have been buffered from the financial crash. Their children are likely to attend private university-level learning centres and go on to become the ‘elite’ of society - lawyers, politicians, judges and bankers. While a proportion of wealthy children have equalities characteristics - such as being disabled - their families have been able to purchase disability AI products, thereby largely avoiding discrimination. State provided children’s services are practically non-existent for these large swathes of the population.

In educational terms, the differences for rich and poor could not be wider. For children from socially disadvantaged backgrounds, school is a penance and access is limited. School hours have been reduced to 9:00-11:30am due to budget cuts and staff shortages, thereby reducing the time to learn.

The curriculum is basic and harsh, focussed on a rigorous testing regime, with no room for creativity or difference. There is little emphasis on technology, health sciences or innovation, which is necessary for today’s job market. Many state schools have been shut down across the country, due to a lack of funding and investment, leaving many children without access to a formal education, and relying on parents’ limited time and ability to home-school. Pupils attending state schools are expected to maintain a high grade point average (a system adopted from the USA), or otherwise face punishment.

Pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds often have difficulty dealing with this highly demanding and competitive education system, and more and more children find themselves excluded from the education system entirely. Children with complex needs who are not sufficiently supported by children’s services often take their frustrations out in school, putting further strain on the education system. Lack of coordination between children’s services and schools means there is little in the way of ‘wrap-around’ help for these children.

For children from wealthier backgrounds, the educational options are quite different. Underperforming state schools have mostly closed down in the South of England, as parents invest in private education. At the fee-paying private schools, young people and their parents demand learning and tuition in computer science, software development and financial management. Soft skills are seen as important to the changing job market. Many young people aim to become self employed and provide artisan bespoke services.

The Independent School Association has pointed out a sharp increase in recent years in the number of children and young people presenting with mental ill-health issues. They said in an article last month, “even though there is so much support given to our children, that in itself can feel like quite an artificial environment at times and for some the ‘small things’ can become ‘big things’ in their lives. Unfortunately, self harming and eating disorders have continued to increase in our schools despite our best efforts”.

Affluent young people are well rehearsed in the kinds of jobs which AI will create and which ones it will replace. Today in 2035, they are entering the world of work demanding a new deal from employers. They know that they have skills which are in demand. Many of those young people have not gone to ‘traditional universities’ which have been dramatically devalued in recent years. They instead go, at a high cost, to highly sought after privately-run learning centres which prepare young people with the required, adaptive skills for tomorrow’s labour market. When they enter the high-end of the labour market, young people from more affluent backgrounds have more choice, in terms of sector and region.

With advancements in technology, people are no longer bound to live where they work, and as such, people with good educations and jobs can move to rural areas for a better quality of life for themselves and their families, and to get away from crime-ridden urban areas. Many affluent people live in ‘gated communities’ where they collectively employ private security firms to protect their properties.

Young people from wealthier backgrounds have populated the senior management ranks of UK branches of American multinationals that have monopolised the ‘gig economy’, such as Uber, Google and Amazon. Through successfully lobbying, they have been able to maintain tax breaks and weaken industrial relations, to ensure the stability of the gig economy. This has resulted in lower amounts of money being invested in public services and weaker trade unions.

For young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, social mobility has ground to a halt. They find it challenging to find permanent, well-paid employment; instead, zero-hours contracts in low-paid industries is the norm. Young people from low-income backgrounds, unable to gain an education, are often forced into the black market, working for criminal gangs who sell illegal drugs and counterfeit goods. Poverty and homelessness are at an all-time high for society’s most vulnerable people with protected characteristics.

Despite automation having eliminated many jobs, those who do work still work long hours for relatively little reward, with little time for their families, self-care or maintaining a work-life balance. Young people educated at state schools lack the skills and abilities to succeed in the fast-growing technological and health sciences industries.

Furthermore, as the workplace has become more based around digital and AI technology and the use of various innovative techniques and devices, this often reinforces existing inequalities, with those from poorer backgrounds less likely to have been educated in these technologies, less likely to own ‘smart’ devices, and less likely to grow up learning how to make the most of the opportunities they offer.

Many young people, particularly from refugee, migrant and socially disadvantaged backgrounds, find it very hard to find out what it is necessary for them to do to access employment and further education opportunities.

Children and young people from disadvantaged backgrounds do not believe that they will have a better quality of life than their parents, and with the odds stacked against them, many have become fearful of the future, triggering a range of mental health disorders. However, the lack of investment in children’s services and mental health services for young people has created a vicious cycle - issues continue to manifest themselves later in life, putting more pressure on the prison system and other services. A sense of hopelessness pervades those communities which are ‘left behind’ and struggle financially; drug use and alcohol dependence has increased amongst the most vulnerable families in society.

Housing has become precarious for those on low incomes. The old, remaining stock of social housing has been increasingly converted into private homes through a new regulation, thus reducing the number of affordable, low-cost homes left in England. People from disadvantaged backgrounds predominantly live in low-quality, rented, temporary accommodation. People living in extreme poverty live on the streets. Home ownership is a luxury of the rich, with homes now costing an average of 10x people’s annual salaries.

Young people growing up in a stable environment with a strong support network of private teachers, doctors and tutors can cope with the world, and often thrive. However, those without this find the transition to adulthood to be very difficult, and often experience stress and anxiety. A large proportion of the child population has a standard of living which cuts them off from many of the opportunities enjoyed by their wealthier peers. Those children and young people facing multiple disadvantages feel fatalistic about their life chances.